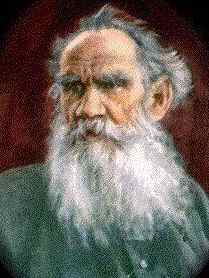

Alexis de Tocqueville in 1850

[From article]

Alexis de Tocqueville was a more prophetic observer of American democracy than even his most ardent admirers appreciate. True, readers have seen clearly what makes his account of American exceptionalism so luminously accurate, and they have grasped the profundity of his critique of American democracy’s shortcomings. What they have missed is his startling clairvoyance about how democracy in America could evolve into what he called “democratic despotism.” That transformation has been in process for decades now, and reversing it is the principal political challenge of our own moment in history. It is implicitly, and should be explicitly, at the center of our upcoming presidential election.

[. . .]

What’s missing in volume 2 of Democracy is concrete, illustrative detail. Volume 1 mines nine months of indefatigable travel that began in May 1831 in Newport, Rhode Island—“an array of houses no bigger than chicken coops”—when the aristocratic French lawyer was still two months shy of his 26th birthday. Tocqueville’s epic journey extended from New York City through the virgin forests of Michigan to Lake Superior, from Montreal through New England, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee by coach, steamboat, and even on foot through snow-choked woods, until he and his traveling companion, Gustave de Beaumont, boarded a steamer for New Orleans. From there, they crossed the Carolinas into Virginia, visited Washington, and returned to New York to embark for home with a trunkful of notes and American histories. Tocqueville had watched both houses of Congress in action and interviewed 200-odd people, ranging from President Andrew Jackson, ex-president John Quincy Adams, Secretary of State Edward Livingston, Senator Daniel Webster, Supreme Court Justice John McLean, and future chief justice Salmon Chase to Sam Houston, a band of Choctaw Indians, and “the last of the Iroquois: they begged for alms.”

[. . .]

Tocqueville didn’t go to America out of blind democratic enthusiasm. “It is very difficult to decide whether democracy governs better, or aristocracy,” he mused:

[. . .]

For the Pilgrims, Tocqueville explained, “Religion looks upon civil liberty as a noble exercise of man’s faculties, and on the world of politics as a realm intended by the Creator for the application of man’s intelligence. . . . Liberty looks upon religion as its comrade in battle and victory, as the cradle of its infancy and divine source of its rights.”

[. . .]

In French, the word is moeurs, meaning manners, morals, core beliefs, and customs—what we would callculture. There are “three major factors that have governed and shaped American democracy,” Tocqueville argued, “but if I were asked to rank them, I would say that physical causes matter less than laws and laws less than mores.”

[. . .]

Most Americans believe [. . .] that “the man who properly understands his own self-interest has all the guidance he needs to act justly and honestly. They believe that every person is born with the faculty to govern himself and that no one has the right to force happiness on his fellow man.” And they believe in human perfectibility, the usefulness of the spread of enlightenment, and the certainty of progress, so that what seems good today will give way tomorrow to something better but as yet unimagined.

Why are your ships not built to last? Tocqueville once asked an American sailor. Naval architecture improves so quickly, the sailor replied, that the finest ship would be obsolete before it wore out. A Silicon Valley engineer would sound the same today.

Not surprisingly, a culture that leaves men free to judge for themselves in religion and politics nurtures independent self-reliance from childhood on. Even in the schoolyard, American children make up their own rules and punish infractions themselves. As adults, they never think of waiting for government to solve everyday problems. If a road gets blocked, they organize themselves to fix it. If they want to celebrate something, they spontaneously join together to make the festivities as fun and grand as possible. Spontaneous nongovernmental associations spring up for furthering “public security, commerce and industry, morality and religion,” Tocqueville marvels,

[. . .]

The typical American is “ardent in his desires, enterprising, adventurous, and above all innovative,” Tocqueville writes. Focused on material gratifications, and seeing idleness as shameful, Americans “think only of ways to change or improve their fortunes,” so that “any new method that shortens the road to wealth, any machine that saves labor, any instrument that reduces the cost of production, any discovery that facilitates or increases pleasure seems the most magnificent achievement of the human mind.”

[. . .]

With the same natural advantages, but different mores, the Spaniards of South America have created some of the most “miserable” nations on earth. Similarly, with a vast wilderness stretching from their doorstep, French settlers in Canada have chosen to “squeeze themselves into a space too small to hold them.”

[. . .]

With the same natural advantages, but different mores, the Spaniards of South America have created some of the most “miserable” nations on earth. Similarly, with a vast wilderness stretching from their doorstep, French settlers in Canada have chosen to “squeeze themselves into a space too small to hold them.”

[. . .]

A century and a half after the Puritan settlers established the little republics of New England, the Constitution carefully preserved the spirit of localism in its federal structure. Congress takes charge of such national matters as foreign relations, war, and international trade, but, lacking any means of knowing the innumerable details of local needs and customs, as Friedrich Hayek later argued about the inevitable failings of centralization, it leaves local matters to the state legislatures and the town meetings.

[. . .]

Tocqueville also saw that the Puritans’ religiosity remained, two centuries later, an undiminished force in American life. It still kept the spiritual realm and its values vibrantly present in minds otherwise materialistic. When an American strikes out into the wilderness to make his fortune, his Bible always goes with him, along with the religious habit of his heart, with its “moral truths.” Tocqueville stresses that religion retains its vitality in America because it has “remained entirely distinct from the political order.” For when religions meddle in politics and take political stands, theirs is but one more mere opinion, subject to disagreement and derision. Thus if clerics make political pronouncements, “they run the risk of not being believed about anything”

[. . .]

With everyone feverishly striving, though, whenever some individual manages to shoot up out of the mass to wealth and power, his fellows respond with envy and wonder if he’s a crook.

So while democracy often gives rise to “a manly and legitimate passion for equality that spurs all men to wish to be strong and esteemed,” it can also lead weak men “to want to bring the strong down to their level”—with such base fervor as ultimately to defeat democracy’s purpose by “preferring equality in servitude to inequality in freedom.”

[. . .]

So while democracy often gives rise to “a manly and legitimate passion for equality that spurs all men to wish to be strong and esteemed,” it can also lead weak men “to want to bring the strong down to their level”—with such base fervor as ultimately to defeat democracy’s purpose by “preferring equality in servitude to inequality in freedom.”

[. . .]

uch intellectual tyranny weighs most heavily on writers and politicians. With no need for the racks and chains of old, democracy’s very mild tyranny “ignores the body and goes straight for the soul,” Tocqueville laments. It leaves the dissident his life, liberty, property, and civic privileges, but it makes them useless to him by making him a pariah, unable to gain the votes or the esteem of his fellow citizens, who will shun him for fear of being shunned themselves. Little wonder, therefore, that America has produced no great writers. And if you want a refutation of the wisdom of crowds—the “theory of equality applied to intelligence,” Tocqueville scoffs—look no further.

[. . .]

That same majoritarian tyranny explains why America’s elected officials are so mediocre. To win votes, they have to flatter public opinion with the obsequiousness of Louis XIV’s most sycophantic courtiers. Andrew Jackson is Tocqueville’s Exhibit A. He “is the slave of the majority,” Tocqueville sneers; “he obeys its wishes and desires and heeds its half-divulged instincts; or rather, he divines what the majority wants, anticipating its desires before it knows what they are in order to place himself at its head.” Like most politicians, he cares only about reelection, so that “his own individual interest supplants the general interest in his mind.”

[. . .]

Given the threat of majoritarian tyranny, such as reigns over U.S. public opinion, such a centralized administration would pose a fearful danger. If the central power could not only issue orders and frame general principles but also carry them out in detail, if it could reach down and seize the individual by the collar, “then liberty would soon be banished from the New World,” Tocqueville asserts.

[. . .]

Physiocrats, whom we remember today as laissez-faire economists—clearly perceived this gigantic governmental machinery and began speculating about the social uses to which it could be put, anticipating not only the whole program of the French Revolution, Tocqueville notes, but also “the subversive theories of what is today known as socialism” and anticipating as well (as he could not know) an almost Leninist totalitarianism. For “socialism and centralization thrive on the same soil; they stand to each other as the cultivated to the wild species of a fruit,” Tocqueville presciently observed.

[. . .]

they had no idea that since Louis XII, French kings had been “dividing men so as the better to rule them” and that by the end of the eighteenth century, “it would have been impossible to find . . . even ten men used to acting in concert and defending their interests without appealing to the central power for aid.” Nor was there even any personal affection to support the king and aristocracy against the overwhelming, all-devouring resentment of the people. So the ancient monarchy came crashing down, and there was nothing to stop the demons “who carried audacity to the point of sheer insanity” and “acted with unprecedented ruthlessness.”

And they could do so because the centralized machinery was in place to carry the reign of terror throughout the nation. “The same conditions which had precipitated the fall of the monarchy made for the absolutism of its successor.” That giant state machinery was there for Napoleon in turn to create his million-man army and set forth to conquer all Europe. And it was still there in 1856, when The Old Regime appeared, and when “the French nation [was] prepared to tolerate in a government that favors and flatters its desire for equality practices and principles that are, in fact, the tools of despotism.”

[. . .]

He liked America’s administrative decentralization—in the 1830s, there were only 12,000-odd U.S. officials, as against France’s 138,000—for its political and cultural effects: “People care about their country’s interests as though they were their own,” he noted. “In its successes they see their own work and are exalted by it.” Matters are different today, now that the federal government has more than 2.7 million employees, state and local governments have 14.3 million, and college students don’t know who won the Civil War or who the U.S. vice president is, and don’t care. Americans have come to resemble the French of Tocqueville’s day, who don’t know what’s happening in their country, are “indifferent to the fate of the place they live in,” and think that the fate of their town and the safety of their streets “have nothing to do with them, that they belong to some powerful stranger called ‘the government.’”

[. . .]

with few Americans even noticing and most unaware of the magnitude of the revolution even today. We created a giant administrative regime, just as Tocqueville feared, composed of such executive-branch agencies as the Interstate Commerce Commission, the Federal Trade Commission, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Federal Elections Commission, and on and on.

[. . .]

These executive-branch agencies legislate by making binding rules for individuals and corporations, and they then adjudicate and punish infractions of them through juryless administrative courts indistinguishable from those run by the French intendants and the Royal Council, lacking due process and usually with no appeal to the real court system. They provide, to use Tocqueville’s words, “an image of justice rather than justice itself.” Nor, as in the ancien régime, can the victims of these agencies’ absolutism sue them or their functionaries. As for the congress whose legislation gave life to these bodies, it is as much a sham as the old French town corporations or magnificently titled nobles. It does little but seek exemptions from the agencies’ rules for corporate donors—whose companies the agencies’ original rationale was to control. And the Constitution that gave life to the government Tocqueville so cherished is, if not dead, then dying.

[. . .]

And when the New Deal took administrative government to new depths of unconstitutionality, Franklin Roosevelt and his brain trust used almost Tocquevillian language in explaining why, in the age of giant corporations more powerful than any individual citizen or mediating institution, only an equally mighty government could protect the wee, timorous, cowering individual. “Thus the industrial class needs to be regulated, supervised, and restrained,” wrote Tocqueville, “and it is natural for the prerogatives of government to grow along with it.” The argument will be, Tocqueville predicted, that “as citizens become weaker and less capable, government must be made more skillful and active, so that society can take upon itself what individuals are no longer capable of doing on their own”—a sentiment that could have come from one of FDR’s fireside chats.

[. . .]

Tocqueville couldn’t find a precise enough name for the new oppressiveness that he saw coming into being— [. . .] “ ‘Despotism’ and ‘tyranny’ will not do.” He groped for a description that would adequately convey the almost otherworldly force he glimpsed in outline, a presence like something out of science fiction, human and yet inhuman.

[. . .]

This new kind of sovereign, “after taking individuals one by one in his powerful hands and kneading them to his liking,” will spread over society “a fine mesh of uniform, minute, and complex rules,” which constrain even the best and brightest. “He does not break men’s wills but softens, bends, and guides them. He seldom forces anyone to act but consistently opposes action. He does not destroy things but rather prevents them from coming into being. Rather than tyrannize, he inhibits, represses, saps, stultifies, and in the end reduces each nation to nothing but a timid and industrious flock of animals, with the government as its shepherd.”

[. . .]

Under the New Deal’s mesh of minute and complex rules, the sovereign—with the Supreme Court’s blessing—punished a farmer in 1942 for growing grain in excess of his allotted quota, to feed to his own livestock. Today the iron cage of administrative rules prevents new businesses from opening, old ones from hiring, doctors from treating patients as they think best, groups of citizens from uttering political speech, even a landowner from moving a pile of sand from one spot to another on his property, purportedly because it could affect a navigable waterway 50 miles away. It slows projects to a crawl, so that building a bridge, a skyscraper, a power plant takes years—whereas in the old America, the Empire State Building rose in 11 months.

And today’s sovereign does force men to act as well as suppressing action, so that nuns must provide their employees with birth control that their religion holds to be sinful, bakers must make cakes celebrating homosexual marriages that their religious beliefs abominate, private colleges must regulate their students’ sex lives, banks must lend to deadbeats. The immense tutelary power has turned private charities into government contractors, so that Catholic Charities or Jewish Social Services are neither Catholic nor Jewish—though most public welfare comes direct from the state, from babies’ milk to old people’s health care and pensions, for which only a minority has paid. As Tocqueville observed, “It is the state that has undertaken virtually alone to give bread to the hungry, aid and shelter to the sick, and work to the idle.” In New York State, where even in the 1830s Tocqueville saw administrative centralization taking form, the sovereign has commanded strictly private clubs to change their admissions criteria, so that even the realm of private association is subject to government power. And whatever traditional American mores defined as good and bad, moral and immoral, base and praiseworthy, the sovereign has redefined and redefined until all such ideas have lost their meaning. Is it any wonder that today’s Americans feel that they have no say in how they are governed—or that they don’t understand how that came about?

Such oppression is “less degrading” in democracies because, since the citizens elect the sovereign, “each citizen, hobbled and reduced to impotence though he may be, can still imagine that in obeying he is only submitting to himself.” Moreover, democratic citizens love equality more than liberty, and the love of equality grows as equality itself expands. Don’t let him have or be more than me. “The only necessary condition for centralizing public power in a democratic society is to love equality or to make a show of loving it. Thus the science of despotism,” Tocqueville despairingly concluded, “can be reduced . . . to a single principle.”

But, wonders Tocqueville, is this what human life is for?

The End of Democracy in America

Tocqueville foresaw how it would come.

Myron Magnet

Spring 2016

No comments:

Post a Comment