October 16, 2007

Curious Censorship

Curious Censorship

Patients are grateful for the altruistic sexual favors Dr. Gorman provided

to

his colleague/patient as chief psychiatrist at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York.

Did this play a role in why Harvard chose him to head the Mass/Harvard

psychiatric combine. (Scott Allen, "A doctor's downfall, McLean's fallout,"

Boston Globe, October 14, 2007)

Gorman's case exemplifies institutionalized abuses of academic

professionals. First is the total lack of accountability. Politicians wonder why

young people refuse to assist police in criminal investigations. Do

psychiatrists snitch on their colleagues? Ahem!

Among academics, credentials provide instant credibility and iron-clad

immunity from scrutiny. The MA Medical Board knew "within days." So why was this

kept secret? To protect Gorman from eager patients?

Enjoying immunity from scrutiny with power and privileges, omniscient

psychiatrists with knowledge of the future are more likely to abuse their power.

Showing how distorted the public discourse on psychiatry is, his own

employees offered sympathy for the man who embarrassed them and abused his

power.

This is symptomatic of the psychiatric boondoggle. It is more rule than

exception. Many psychiatrists refuse to provide sexual favors for their love

starved patients. But they abuse their power relationships in other ways. What

do these charlatans know that the rest of the human race does not? Where did

they get their superior knowledge of morality? From doctors like Gorman? His

abuses of power are rewarded by the New York psychiatric establishment. He is

still qualified to teach other psychiatrists so that they can adopt his

standards of care.

Dr. Gorman poster boy for "The Cheating Culture."

Roy Bercaw, Editor ENOUGH ROOM

A doctor's downfall, McLean's fallout

Sex secret kept quiet for a year

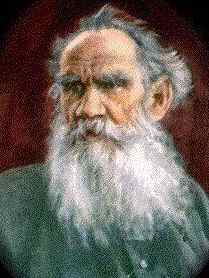

Dr. Jack Gorman admitted having sex with a patient.

By Scott Allen,

Boston Globe Staff

October 14, 2007

One Monday morning in April 2006, Dr. Jack M. Gorman, new president of McLean

Hospital in Belmont, simply stopped showing up for work.

For days, increasingly worried hospital officials didn't know what had become of

their leader until, finally, a family member answering a call at his New York

City home revealed that Gorman was in a hospital intensive care unit being

treated for an ailment that the person wouldn't reveal.

So began the spectacular downfall of a highly respected psychiatrist who had

arrived at the Harvard-affiliated hospital just a few months earlier to take on

one of the most influential jobs in mental health care.

Over the next few days, officials at McLean learned that Gorman had, like so

many patients at the renowned psychiatric hospital, attempted suicide. But their

initial sympathy for a sick man turned to horror when they learned, from a legal

document delivered in mid-May, why he had taken such a desperate measure. The

married father of two had brought a shameful secret with him to Massachusetts:

He had engaged in a long-term sexual relationship with a New York patient.

Any romantic involvement with a patient is strictly forbidden in psychiatry, and

Gorman's entanglement would drive him to self- destruction, resignation, and

disgrace - finally spattering McLean's reputation as well when it became public

last week.

PDF OF GORMAN DOCUMENTS: The investigation report, letter to MacLean staff, and

New York suspension order

For more than 16 months, both sides kept the whole episode quiet, saying only

that Gorman had left McLean in May 2006 for undisclosed "personal and medical

reasons." In reality, Gorman stopped coming to work because he had overdosed on

antidepressant pills after his patient, distraught over Gorman's move to

Massachusetts, hired a lawyer and threatened to expose their relationship,

according to people directly involved in the case. Though the pills hadn't

killed him, Gorman needed weeks in the hospital to recuperate.

Now, McLean Hospital is publicly facing the fall-out from one of the more tawdry

chapters in its nearly 200-year history. Last week, Partners HealthCare, the

parent company of McLean, conducted a review of Gorman's brief tenure to

reassure state regulators that he had not sexually abused patients there.

Gorman didn't treat any individual patients at McLean, concluded Partners chief

operating officer Thomas P. Glynn, both because he was too busy as president and

because he only obtained a license to treat Massachusetts patients a few days

before he departed. Glynn said last week's review and an internal investigation

last year did not turn up new allegations against him. In addition, he said that

McLean notified Massachusetts medical regulators about the sexual misconduct

within days of Gorman's departure.

On Friday, hospital officials stressed in a letter to staff and patients that

the hospital did nothing wrong in its handling of Gorman's problems and that the

only apparent victim was the patient, a woman who was also a colleague of Gorman

when he was in New York.

"We appreciate that this may be surprising and disturbing information for many

of you," wrote McLean's chairwoman of the board, Kathleen F. Feldstein, and new

president, Scott L. Rauch. "Our hope is that we can continue to focus on the

important work of caring for our patients, training mental health professionals

and advancing scientific knowledge, as we have always done."

But the leaders of McLean and Partners face lingering questions from the many

people connected to McLean who feel betrayed by their former chief executive:

How could they have hired the doctor in the first place? And why didn't they

speak up earlier about Gorman's misconduct?

Gorman, 55, inspired great hope when McLean and Partners announced that they had

lured him away from New York City's Mount Sinai School of Medicine in October

2005. After a two-year search for someone to take on the newly created job of

top psychiatrist for all of Partners HealthCare, they had landed a highly

respected authority on anxiety disorders, depression, and schizophrenia who had

won numerous awards for his research. He was also a seasoned administrator and

the author of books on psychiatry for a general audience, making him a seemingly

ideal candidate to be the face of both McLean and of Harvard University

psychiatry.

Almost immediately, Gorman struggled to adjust to his new life. His wife and

daughters didn't relocate with him, resulting in lots of travel back and forth

to New York at a time when he was trying to understand the vast research and

treatment program he was now running. At the same time, bureaucratic delays kept

Gorman from obtaining his medical license in Massachusetts until April 5, 2006,

meaning he could not legally prescribe medications for patients at McLean during

the first few months of his tenure.

Still, people said they were impressed by Gorman's intellect and sense of

purpose in his new position. As one staff member put it, "He just radiated

hope."

As a result, when Gorman did not report for work on Monday, April 24, 2006, his

staff did not automatically assume something was amiss. However, Glynn said

worries began to mount when staff members called Gorman's home and did not get a

clear explanation of his whereabouts. "Finally, I think it was maybe at the

beginning of May when we were finally told by someone that he was in the

hospital for personal and health issues," said Glynn.

Over the next few days, McLean and Partners officials learned that Gorman had

attempted suicide and that he was in the hospital for serious gastrointestinal

problems. A person close to Gorman said he had taken numerous tricyclic

antidepressants, 1950s vintage drugs still widely used in the Prozac era that

are known to be poisonous at high doses.

The fact that their new chief executive had attempted to kill himself raised

serious doubts about whether he could continue, Glynn said, but as late as May

16, 2006, the hospital was still treating Gorman as a sick man deserving of

sympathy. At a fund-raiser on that day, McLean chairwoman Feldstein urged the

audience to send Gorman their best wishes for a speedy recovery so that he could

return to McLean.

But immediately after that event, Partners officials said, they received a legal

document outlining Gorman's relationship with the woman dating to 2003. The

document said that the woman had been both a patient and a colleague, traveling

to conferences with Gorman while also getting psychiatric care from him. The

relationship had soured after he accepted the McLean job, and she had hired a

Boston lawyer to file a possible lawsuit.

Suddenly, the suicide attempt made sense and, Glynn said, it was clear that

Gorman had to leave immediately.

"We needed to take action to put McLean and Partners psychiatry on a safe

footing again. That entailed accepting Dr. Gorman's letter of resignation," said

Glynn,, noting that Gorman's job also put him in charge of psychiatry at the

other Harvard-affiliated hospitals in the Partners system, including

Massachusetts General Hospital.

But Gorman contends that, by May 18, he had already sent a letter of resignation

to McLean in which he deliberately avoided disclosing his inappropriate

relationship or suicide attempt in order to protect the hospital's reputation.

"One of Dr. Gorman's primary motivations in doing so was to protect and spare

McLean any embarrassment because he was extremely grateful, and remains so, for

the extraordinary opportunity which they had entrusted to him," said Lou

Colasuonno, a communications consultant representing Gorman. However, when the

hospital was reluctant to let Gorman step down, he reluctantly told them about

the "underlying issue" for his departure, Colasuonno said.

Colasuonno also said that, since Gorman's resignation, he has tried to atone for

his mistakes, even reporting himself to medical regulators in New York for

punishment. In a statement last week, Gorman said that he "voluntarily

acknowledged any mistakes" and "paid a huge personal price" as a result.

It was Gorman's decision to contact the New York Board of Professional Medical

Conduct that finally brought the episode to public attention. Earlier this

month, the board finally acted on what Gorman told them, posting on its website

that his medical license had been indefinitely suspended for "inappropriate

sexual contact" with a patient.

Looking back, Glynn said the presidential search committee talked extensively

with Gorman's colleagues, friends, and associates at Mount Sinai, but no one

suggested that he was engaged in unethical conduct. If there had been a problem,

Glynn said, the hospital had two other finalists they could have selected

instead. He said Partners brought in an outside law firm after Gorman's

departure to review the candidate selection methods for any potential flaws; the

firm found none.

"In this day and age, you have to make the extra effort to look at every nook

and cranny of a major appointment before you proceed," said Glynn. "But, even

with that level of diligence, it doesn't mean you won't get a surprise."

Janet Wohlberg of Williamstown, who runs an Internet-based help line called the

Therapy Exploitation Link Line, said she's not surprised that any rumors about

Gorman's inappropriate relationship did not surface during the presidential

search.

"People don't really want to believe these things about their colleagues,"

Wohlberg said, and, even if people suspect misconduct, they're unlikely to say

anything to a potential employer without proof. "I think the fault lies squarely

with the perpetrator," said Wohlberg.

For his part, Gorman has apologized for past misconduct, but he is already

rebuilding his career. He lists himself as an adjunct professor at Mount Sinai

on publicity materials related to a newly revised version of his book, "The

Essential Guide to Psychiatric Drugs," which hit bookstores in the last few

weeks.

Scott Allen can be reached at allen@globe.com.

Patients are grateful for the altruistic sexual favors Dr. Gorman provided

to

his colleague/patient as chief psychiatrist at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York.

Did this play a role in why Harvard chose him to head the Mass/Harvard

psychiatric combine. (Scott Allen, "A doctor's downfall, McLean's fallout,"

Boston Globe, October 14, 2007)

Gorman's case exemplifies institutionalized abuses of academic

professionals. First is the total lack of accountability. Politicians wonder why

young people refuse to assist police in criminal investigations. Do

psychiatrists snitch on their colleagues? Ahem!

Among academics, credentials provide instant credibility and iron-clad

immunity from scrutiny. The MA Medical Board knew "within days." So why was this

kept secret? To protect Gorman from eager patients?

Enjoying immunity from scrutiny with power and privileges, omniscient

psychiatrists with knowledge of the future are more likely to abuse their power.

Showing how distorted the public discourse on psychiatry is, his own

employees offered sympathy for the man who embarrassed them and abused his

power.

This is symptomatic of the psychiatric boondoggle. It is more rule than

exception. Many psychiatrists refuse to provide sexual favors for their love

starved patients. But they abuse their power relationships in other ways. What

do these charlatans know that the rest of the human race does not? Where did

they get their superior knowledge of morality? From doctors like Gorman? His

abuses of power are rewarded by the New York psychiatric establishment. He is

still qualified to teach other psychiatrists so that they can adopt his

standards of care.

Dr. Gorman poster boy for "The Cheating Culture."

Roy Bercaw, Editor ENOUGH ROOM

A doctor's downfall, McLean's fallout

Sex secret kept quiet for a year

Dr. Jack Gorman admitted having sex with a patient.

By Scott Allen,

Boston Globe Staff

October 14, 2007

One Monday morning in April 2006, Dr. Jack M. Gorman, new president of McLean

Hospital in Belmont, simply stopped showing up for work.

For days, increasingly worried hospital officials didn't know what had become of

their leader until, finally, a family member answering a call at his New York

City home revealed that Gorman was in a hospital intensive care unit being

treated for an ailment that the person wouldn't reveal.

So began the spectacular downfall of a highly respected psychiatrist who had

arrived at the Harvard-affiliated hospital just a few months earlier to take on

one of the most influential jobs in mental health care.

Over the next few days, officials at McLean learned that Gorman had, like so

many patients at the renowned psychiatric hospital, attempted suicide. But their

initial sympathy for a sick man turned to horror when they learned, from a legal

document delivered in mid-May, why he had taken such a desperate measure. The

married father of two had brought a shameful secret with him to Massachusetts:

He had engaged in a long-term sexual relationship with a New York patient.

Any romantic involvement with a patient is strictly forbidden in psychiatry, and

Gorman's entanglement would drive him to self- destruction, resignation, and

disgrace - finally spattering McLean's reputation as well when it became public

last week.

PDF OF GORMAN DOCUMENTS: The investigation report, letter to MacLean staff, and

New York suspension order

For more than 16 months, both sides kept the whole episode quiet, saying only

that Gorman had left McLean in May 2006 for undisclosed "personal and medical

reasons." In reality, Gorman stopped coming to work because he had overdosed on

antidepressant pills after his patient, distraught over Gorman's move to

Massachusetts, hired a lawyer and threatened to expose their relationship,

according to people directly involved in the case. Though the pills hadn't

killed him, Gorman needed weeks in the hospital to recuperate.

Now, McLean Hospital is publicly facing the fall-out from one of the more tawdry

chapters in its nearly 200-year history. Last week, Partners HealthCare, the

parent company of McLean, conducted a review of Gorman's brief tenure to

reassure state regulators that he had not sexually abused patients there.

Gorman didn't treat any individual patients at McLean, concluded Partners chief

operating officer Thomas P. Glynn, both because he was too busy as president and

because he only obtained a license to treat Massachusetts patients a few days

before he departed. Glynn said last week's review and an internal investigation

last year did not turn up new allegations against him. In addition, he said that

McLean notified Massachusetts medical regulators about the sexual misconduct

within days of Gorman's departure.

On Friday, hospital officials stressed in a letter to staff and patients that

the hospital did nothing wrong in its handling of Gorman's problems and that the

only apparent victim was the patient, a woman who was also a colleague of Gorman

when he was in New York.

"We appreciate that this may be surprising and disturbing information for many

of you," wrote McLean's chairwoman of the board, Kathleen F. Feldstein, and new

president, Scott L. Rauch. "Our hope is that we can continue to focus on the

important work of caring for our patients, training mental health professionals

and advancing scientific knowledge, as we have always done."

But the leaders of McLean and Partners face lingering questions from the many

people connected to McLean who feel betrayed by their former chief executive:

How could they have hired the doctor in the first place? And why didn't they

speak up earlier about Gorman's misconduct?

Gorman, 55, inspired great hope when McLean and Partners announced that they had

lured him away from New York City's Mount Sinai School of Medicine in October

2005. After a two-year search for someone to take on the newly created job of

top psychiatrist for all of Partners HealthCare, they had landed a highly

respected authority on anxiety disorders, depression, and schizophrenia who had

won numerous awards for his research. He was also a seasoned administrator and

the author of books on psychiatry for a general audience, making him a seemingly

ideal candidate to be the face of both McLean and of Harvard University

psychiatry.

Almost immediately, Gorman struggled to adjust to his new life. His wife and

daughters didn't relocate with him, resulting in lots of travel back and forth

to New York at a time when he was trying to understand the vast research and

treatment program he was now running. At the same time, bureaucratic delays kept

Gorman from obtaining his medical license in Massachusetts until April 5, 2006,

meaning he could not legally prescribe medications for patients at McLean during

the first few months of his tenure.

Still, people said they were impressed by Gorman's intellect and sense of

purpose in his new position. As one staff member put it, "He just radiated

hope."

As a result, when Gorman did not report for work on Monday, April 24, 2006, his

staff did not automatically assume something was amiss. However, Glynn said

worries began to mount when staff members called Gorman's home and did not get a

clear explanation of his whereabouts. "Finally, I think it was maybe at the

beginning of May when we were finally told by someone that he was in the

hospital for personal and health issues," said Glynn.

Over the next few days, McLean and Partners officials learned that Gorman had

attempted suicide and that he was in the hospital for serious gastrointestinal

problems. A person close to Gorman said he had taken numerous tricyclic

antidepressants, 1950s vintage drugs still widely used in the Prozac era that

are known to be poisonous at high doses.

The fact that their new chief executive had attempted to kill himself raised

serious doubts about whether he could continue, Glynn said, but as late as May

16, 2006, the hospital was still treating Gorman as a sick man deserving of

sympathy. At a fund-raiser on that day, McLean chairwoman Feldstein urged the

audience to send Gorman their best wishes for a speedy recovery so that he could

return to McLean.

But immediately after that event, Partners officials said, they received a legal

document outlining Gorman's relationship with the woman dating to 2003. The

document said that the woman had been both a patient and a colleague, traveling

to conferences with Gorman while also getting psychiatric care from him. The

relationship had soured after he accepted the McLean job, and she had hired a

Boston lawyer to file a possible lawsuit.

Suddenly, the suicide attempt made sense and, Glynn said, it was clear that

Gorman had to leave immediately.

"We needed to take action to put McLean and Partners psychiatry on a safe

footing again. That entailed accepting Dr. Gorman's letter of resignation," said

Glynn,, noting that Gorman's job also put him in charge of psychiatry at the

other Harvard-affiliated hospitals in the Partners system, including

Massachusetts General Hospital.

But Gorman contends that, by May 18, he had already sent a letter of resignation

to McLean in which he deliberately avoided disclosing his inappropriate

relationship or suicide attempt in order to protect the hospital's reputation.

"One of Dr. Gorman's primary motivations in doing so was to protect and spare

McLean any embarrassment because he was extremely grateful, and remains so, for

the extraordinary opportunity which they had entrusted to him," said Lou

Colasuonno, a communications consultant representing Gorman. However, when the

hospital was reluctant to let Gorman step down, he reluctantly told them about

the "underlying issue" for his departure, Colasuonno said.

Colasuonno also said that, since Gorman's resignation, he has tried to atone for

his mistakes, even reporting himself to medical regulators in New York for

punishment. In a statement last week, Gorman said that he "voluntarily

acknowledged any mistakes" and "paid a huge personal price" as a result.

It was Gorman's decision to contact the New York Board of Professional Medical

Conduct that finally brought the episode to public attention. Earlier this

month, the board finally acted on what Gorman told them, posting on its website

that his medical license had been indefinitely suspended for "inappropriate

sexual contact" with a patient.

Looking back, Glynn said the presidential search committee talked extensively

with Gorman's colleagues, friends, and associates at Mount Sinai, but no one

suggested that he was engaged in unethical conduct. If there had been a problem,

Glynn said, the hospital had two other finalists they could have selected

instead. He said Partners brought in an outside law firm after Gorman's

departure to review the candidate selection methods for any potential flaws; the

firm found none.

"In this day and age, you have to make the extra effort to look at every nook

and cranny of a major appointment before you proceed," said Glynn. "But, even

with that level of diligence, it doesn't mean you won't get a surprise."

Janet Wohlberg of Williamstown, who runs an Internet-based help line called the

Therapy Exploitation Link Line, said she's not surprised that any rumors about

Gorman's inappropriate relationship did not surface during the presidential

search.

"People don't really want to believe these things about their colleagues,"

Wohlberg said, and, even if people suspect misconduct, they're unlikely to say

anything to a potential employer without proof. "I think the fault lies squarely

with the perpetrator," said Wohlberg.

For his part, Gorman has apologized for past misconduct, but he is already

rebuilding his career. He lists himself as an adjunct professor at Mount Sinai

on publicity materials related to a newly revised version of his book, "The

Essential Guide to Psychiatric Drugs," which hit bookstores in the last few

weeks.

Scott Allen can be reached at allen@globe.com.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment